“NoGo” – Creating a nature-bank to guarantee human well-being.

Part 3 (concluding)—NoGo Now!

“NoGo” is a principle of nature conservation that affirms what should be obvious, that formally protected nature areas (such as national parks and wildlife refuges) and indigenous, natural sacred sites and community conservation areas, should be off-limits to industrial, commercial exploitation such as mining, drilling, and logging. After all, formal designations should result in actual protections, right?

The World Parks Congress (WPC, Sydney, 2014) was the first venue for the ‘NoGo consortium’ to test its message and influence, and to begin a concerted push for the NoGo principle to more-fully enter mainstream global conservation parlance, policy, and practice. The controversy around it continued, with more than one comment from some in the conservation field that they “could not risk alienating their corporate partners”. However, the terminology was recorded in two places within the detailed report of WPC – “The Promise of Sydney” (see streams 6 and 7) – though it was omitted from the “Vision Statement” (the introductory/overview section), an otherwise stronger-than-normal statement from the IUCN that sounded a warning bell on exploitation run amok.

Photo: Paul Dutton. Sand dredge mining for titanium threatened Lake St. Lucia National Park (South Africa) and stimulated a public movement that re-created this area as the iSimangaliso Wetland park, a UNESCO World Heritage area.

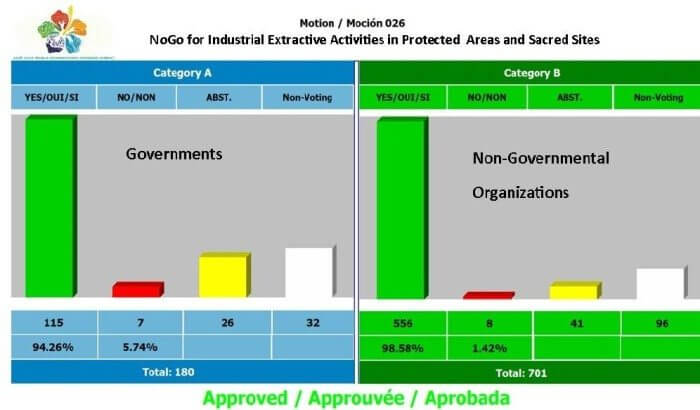

The consortium was emboldened and strengthened by this, and then further encouraged when the IUCN Council (the highest elected advisory body within the International Union for the Conservation of Nature) asked WILD’s Vice President for Policy to produce a briefing paper on NoGo policy. Aiming towards the World Conservation Congress (WCC) scheduled for September of 2016, the Council then drafted a proposed motion on this principle for consideration by IUCN members during the WCC, a motion largely focused on the importance of this principle for meeting the global biodiversity targets of the Convention on Biodiversity, a United Nations protocol with 196 State Members (not including a very few countries such as the United States). This Council-drafted motion was ultimately merged with a similar but stronger motion proposed by the NoGo consortium (that focused on all protected areas and sacred sites) to become “Motion 026”, and one of only 14 out of 106 WCC plenary motions identified as controversial enough to require floor debate and vote.

After years of often-acrimonious controversy and six months of combative commentary leading up to the 2016 WCC (much of it fueled by “conservationists” consulting to extractive companies), the NoGo principle as embodied in Motion 026 was scheduled as the first of the controversial motions to be opened for plenary floor debate and vote. During the usual lobbying period in the few days leading up to the floor debate, several key governmental delegations had serious reservations and many face-to-face meetings were held. The conversations were low-intensity (on the most part) and reasonably constructive. In general, there seemed to be little highly-organized opposition…something the NoGo consortium found hard to fathom.

In an almost anti-climactic turn of events, when the floor was opened to Motion 026, no comments were offered, the vote was thereby taken, and the motion approved by an overwhelming majority of both governments and NGOs (the IUCN regulations require approval in both “houses”). Of 148 voting governments, only 7 voted no; of 605 voting NGOs, only 8 voted no.

What does this mean? In summary, here are two perspectives:

- What it may mean is that a major change is afoot within the formal conservation sector. After 25 years of a dominant strategy to work almost entirely inside governments and the private sector to “green the supply chain,” “design and implement best practices,” etc, the reality is emerging that this cannot be the sole strategy because it has largely failed to halt destruction. So, perhaps we now see a shift in conservation attitude and practice, and the recognition that we need more nature protection and less industry if we’re going to deal with major effects of the Anthropocene era – the accelerating biodiversity crisis (the 6th Great Extinction) and the already well-underway, climate change crises. Motion 026 marks what we hope is the beginning of the swing in the pendulum.

- What it certainly means is that the largest, most global, member-driven, conservation body in the world has accepted and will now promulgate into policy the principle that areas designated for conservation protection or as sacred natural areas for Indigenous Peoples should be considered off-limits to “environmentally damaging, industrial extractive activities and infrastructure.”

Jægersborg Dyrehave, a forest park located north of Copenhagen, is known for its mixture of huge, ancient oak trees and large populations of red and fallow deer. Dyrehaven is maintained as natural forest, with the emphasis on the natural development of the woods over commercial forestry.

Once an IUCN motion is adopted it becomes a ‘resolution.’ Though not legally-binding instruments, IUCN resolutions are used a great deal by policy makers inside and outside the government sector, are considered conservation consensus or even best-practice, and have great impact and significant usefulness. They particularly inform international conventions and protocols, many national and sub-national governments, and affect innumerable specific issues from local to global. The final, approved language can be found here.

This is a win for wild nature and people. It honors both the necessity for and spirit of nature protection – a statement for the well-being of all life. And, it is just the next step along the trail towards a planet in which Nature Needs Half and Half Earth are the operating norms, and where people and nature are partners, not polarities.

In case you missed it, read:

- NoGo Part 1 – So, you thought parks and other special protected areas were actually protected?

- NoGo Part 2 – “Sustainability” needs to respect appropriate boundaries

The WILD Foundation acknowledges with gratitude and respect the support and vision of the Weeden Foundation.