The worms do not care the color of your skin…

The WILD Foundation stands in solidarity with our brothers and sisters of color around the world. We support those joining hands in the fight against racism and violence and are proud of our active legacy working across culture, race, and institutions to create a more equitable and diverse conservation sector in which we work. Our team continues this legacy and we are actively listening for how we can assist in the creation of a healthy, sustainable, and just world. Environmental justice depends on human justice. You cannot have a world that protects nature without protecting its people first. Black Lives Matter. In the 1960s South Africa of Apartheid, when non-white people were segregated and subjugated, our founders (Magqubu Ntombela and Ian Player) worked together in the wilderness and, with a team of many races and cultures, saved the white rhino from extinction. But racial inequity didn’t end with abolishment of Apartheid in South Africa or the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, therefore the WILD team is dedicated to continuing our mission for all races, cultures, species, and ecosystems. View our full statement in support of #BlackLivesMatter here >

We convey to you here our commitment to this issue through a true story told by our President, Vance Martin, who has 45+ years of working across cultural and institutional barriers.

The soft crackling and gentle glow of the small fire on the banks of the iMfolozi River was insignificant in the powerful presence of the African night. The sky was bursting with stars, with lions roaring in the distance, as two men also listened to the splashing of a bushbuck as it crossed the river.

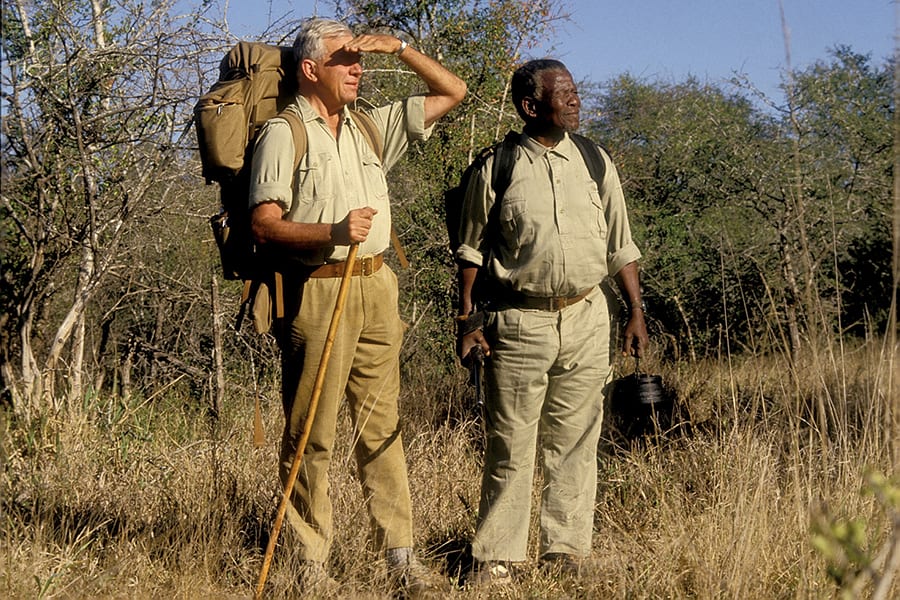

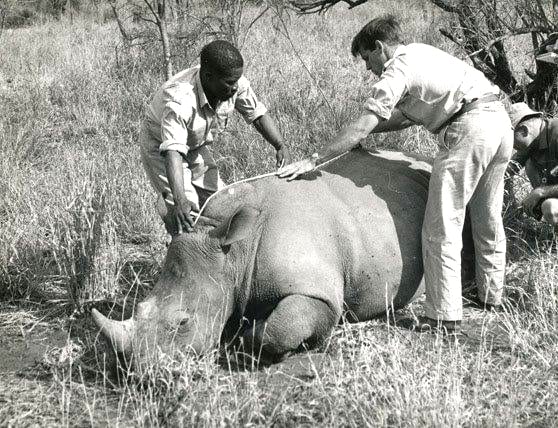

The future co-founders of the WILD Foundation, Ian Player (a white, senior wildlife conservator) and Zulu elder, Magqubu Ntombela (Ian’s mentor/brother/tracker), quietly discussed the difficulties around and ahead of them, chief among these saving the white rhino from extinction. Only one small population remained in the small redoubt of Africa’s oldest protected area, the iMfolozi Game Reserve (South Africa). The need was clear to them, but not the process, for no one had ever moved, at-scale, a very large and sometimes temperamental mammal to far-away locations where they would be safer from the potential threats of disease and poaching. What’s more, this was occurring during the era of apartheid, the South African, white-ruled system of legal segregation of races and the (often violent) subjugation of non-white peoples.

Ian told me this story some 25 years later as he, Magqubu, and I sat on the banks of the same river, around the soft crackling and in the fragrance of the small fire made of tamboti wood. “We had to move them,” Ian said, “because a virus could come into the Reserve and wipe them all out. They are safer in small groups, further apart.” They accomplished their goal with a multi-racial group of scientific experts, professional wildlife managers, and local game scouts who could not read or write. They worked together on the ground, in the hot African bush, to develop the first techniques, drugs, and processes that allowed many white rhino to be moved throughout Africa and around the world, and for its population to grow from a few hundred to almost 25,000 by the year 2010. The racially, economically, and culturally diverse team worked with, learned from, and respected each other for the common good of saving an ancient species of animal.

Sound familiar? The need for safety from disease, extinction, and violence… in the social context of racial injustice? There are lessons we can learn, now, from what occurred then. I did.

As a young man in my mid-30’s, I looked at the elderly Magqubu as we sat there on the riverbank, quietly singing praise songs as he often did. I asked him how we could help change the unjust law of apartheid. With Ian translating, the old man spoke simply in his typical, low and rumbling voice. “When you die and are buried in the ground, the worms do not care the color of your skin. When we understand nature, our life is strong. It is simple and difficult. But we must always hope and do what is right.” Nine years later, after 27 years in prison and in a violence-free transition of power, Nelson Mandela was elected President of South Africa. I am reminded today of Mandela’s reply when asked how he survived those years in prison: “Hope is a powerful weapon, and no power on earth can deprive you of it.”

And here we are now, 2020. After 400 years of human suffering perpetrated by a culture of white supremacy and in the midst of an existential crises – the climate and extinction emergencies that threaten human survival – a man was murdered by those charged to protect and serve. His name was George Floyd, the most recent victim on a list of many.

But protect what? And serve who?

Because you read this blog, you likely understand: the importance of protecting nature in service to humanity; that peace and prosperity are possible only from a respectful relationship with nature; and that such a reality can never be made manifest if we don’t also respect and protect each other.

Where do we go from here? Those who have been the target of systemic racism and other violence are telling us how to proceed. I suggest we listen respectfully, hopefully, and, most importantly, actively. More specifically, two thoughts.

Ubuntu. Ian Player and Magqubu established WILD, and they infused our organization with the same principles and practice they used to save the white rhino. They worked together for the common good, blind to racial and cultural differences — they followed the example of the worm. By doing so, they practiced ubuntu, that very special Bantu philosophy that asserts the power of mutual respect — “I am because you are” – and confirms a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity, and should also connect humanity to all of nature. What also comes to mind in the contemporary western world is the growing awareness of ‘co-liberation’ — we are not free until we are all free… and humanity is not free until enough nature is wild and free.

Hope. Many years ago, I stopped being optimistic because it seemed empty to me and I wanted engagement, connection, and reason. Vaclav Havel captured my feeling perfectly: “Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out.”

And certainly Madiba (Mandela) got it right when he confirmed that life can strip you of everything except your attitude, and that the attitude of hope is indeed very powerful. But there is more. To me, hope is active, it only fully manifests in doing. In fact, I subscribe fully to that which Kris Tompkins (Tompkins Conservation) asserts, that people are only deserving of hope when they act for the common good.

Acting for the common good needs to be our common goal. As we face our common challenges— racial injustice, climate change, pandemics, and extinction — achieving this goal means viewing the world through connections rather than differences, and then acting accordingly. We cannot be silent.

Magqubu’s words echo loudly in my ears today.

Read Next

Swedish Forest Company SCA’s Exit from FSC Certification

Swedish forest company, SCA, is leaving the Forest Stewardship Council—undermining Indigenous rights, climate action, and opening the door to ecological harm.

Investing in Tomorrow: CoalitionWILD’s Mentorship Motion

For decades, conservation has relied heavily on the deep wisdom and technical expertise of seasoned practitioners. Their hard-won knowledge has protected landscapes, endangered species, and cultural heritage across the globe. Yet as we stand on the brink of unprecedented ecological tipping points, there is an urgent need to cultivate the next wave of leadership—one that is agile, inclusive, and ready to inherit the mantle of responsibility.

Protecting the Sápmi Forest

Boreal forests are the largest land-based carbon sink yet Sweden is deforesting its old growth trees at a faster rate than the deforestation of the Amazon.

BECOME A MEMBER

BECOME A MEMBER

Join the WILD tribe today!

0 Comments