It took us 27 days and 1,490 km to pass through Namibia. And as it so often happens on long journeys, individual days tend to merge the passage of time. As we left the Dobe border post for the Okavango wetlands in Botswana, recollections of those first steps as we ventured out from Rocky Point on the wild and wind-swept beaches of the Skeleton Coast seemed an age ago.

It took us 27 days and 1,490 km to pass through Namibia. And as it so often happens on long journeys, individual days tend to merge the passage of time. As we left the Dobe border post for the Okavango wetlands in Botswana, recollections of those first steps as we ventured out from Rocky Point on the wild and wind-swept beaches of the Skeleton Coast seemed an age ago.

However, while the heat and physical endeavour may have blurred certain senses, it has nonetheless been an incredible journey of discovery and learning. Our experiences have been made all the more gratifying and complete through the extraordinary people we have met along the way. All showed immense hospitality and gave so openly of their knowledge and expertise. From all of us involved in TRACKS, many thanks indeed, and to Namibians one and all, you are blessed with a magnificent country.

There is so much to relate, but for this blog, I will keep it to some of the more notable conservation and wildlife management issues. The most impressive aspect has been to see firsthand the success and vitality of Namibia’s Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) policies. Bound up in what are commonly referred to as conservancies, these natural resource management entities have over the last three decades become the backbone of Namibia’s conservation efforts across the entire northern and central regions of the country.

Tasked with the dual challenges of conserving the nation’s ecosystems and biodiversity as well as promoting development and reducing poverty levels, planning began back in the 1980’s. This work was pioneered by various NGO’s, most notably the Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRNDC) and WWF. Their efforts received significant traction after independence in 1990 when the new government, through the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, bought into the vision. New legislation was introduced in 1995, which meant that CBNRM became the official policy of the Namibian government and for the first time rural and traditional communities, representing approximately 41% of the land, now had real ownership and responsibility for their wildlife resources.

Today there are over 70 conservancies, either fully registered, or in the process of being registered. These cover over 135 000 sq km, or approximately 16% of the country, and are home to about 240 000 people. In the process, various other stakeholders, including a host of NGO’s and other government ministries, as well as the eco-tourism sector, have also fully embraced the policies.

Another significant feature of the conservancies is those situated in the north-western regions of Kunene and Kaokoland now form an uninterrupted corridor linking the Iona-Skeleton Coast TFCA with Etosha Pan National Park. This is increasingly becoming a vital link between wet and dry season ranges for both wildlife and livestock.

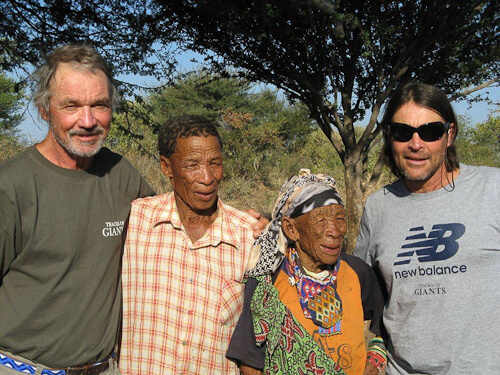

And then in the far eastern regions around Tsumkwe, the three San-managed conservancies have also become significant success stories. Forming a corridor with Khaudum Game Park, which in turn links into the wildlife-rich regions of Ngamiland in northern Botswana, the San are now regaining control over some of their ancestral lands. This has restored a strong sense of pride and purpose to the lives of a group of people that have otherwise been appallingly treated by all governments across the sub-continent.

Given the global recognition and praise for these policies, Namibia’s approach must surely hold something for other states across Africa grappling with similar issues? While the specifics to each region and country will differ, the vision involving awareness, consultation, education, ownership and empowerment is a sound and powerful one.

Despite the successes, disputes and challenges remain. The different objectives and priorities brought to respective initiatives by the numerous stakeholders involved cropped up most commonly. Not unlike that of landlord and tenant, or the supply and demand chain common to the industrialized world, the pricing of assets and the scope of usage have become the markers for many of these disagreements. The next step must surely involve a more integrated approach.

Not unexpectedly, the age-old conflicts that exist between humans and wild animals outside the urban areas continue. Whether amidst those living a life of subsistence or the commercial agricultural world, tales of competition for space and water are commonly heard. There are however notable distinctions. For the rural communities, these often play out literally as struggles involving life or death: elephants trampling harvestable crops or baboons devastating newly planted seedbeds may mean a season of hunger, while people get killed every year by predators, elephants or hippo. For the commercial cattle rancher, which is the primary agricultural activity in these northern regions, these conflicts are seemingly more about time and money.

Within both constituencies, there appears to be a wide range of opinions as to how best these conflicts should be managed. While removing the offending animals remains a popular option, it was heartening to hear many conservancy members and farmers reject this choice on the basis that wildlife should not always bear the direct blame. Some spoke of land-owners needing to take more responsibility over their livestock and crops, and better compensation packages were also a preferred solution.

Particularly gratifying has been the obvious interest and enthusiasm for the newly created KAZA transfrontier park. Incorporating almost the entire Caprivi Strip, Khaudum Game Park and the large surrounding conservancies, these Namibian components to what will be the world’s largest protected area form a vital western Kalahari arm. Given what Namibia has already achieved with its corridor conservation initiatives, it is not beyond possibility that these regions are next linked to Etosha Pan. Why not?